Values How to Find and Live by Them

Table of Contents

- How to Find and Live by Your Values

- What are Values?

- Characteristics of Values

- Defining Values

- Key Characteristics of Values

- Core Questions Values Address

- Values vs. Psychological Needs vs. Preferences

- Schwartz's Values Wheel

- Instrumental and Terminal Values

- Hierarchy of Values

- Values Conflict

- Carol Ryff's Six Dimensions of Psychological Well-being

- Aristotle's Golden Mean as Virtue

- Values and Your Relationships

- A Case Study in Values Clash

- The Importance of Aligning Values

- Navigating the Complexity of Values in Relationships

- Revealing Our Values Through Relationships

- The Role of Communication and Self-awareness

- Compatibility and Future Outlook

- The Clash of Values in Relationships

- Identifying and Navigating Values in Relationships

- Understanding Compatibility Through Values

- Where Do Values Come From?

- Identifying Your Core Values

- How to Change Your Values

- Lessons and Takeaways

- What We Learned

- Next Steps

How to Find and Live by Your Values

What are Values?

Characteristics of Values

Defining Values

Let's get into the nitty-gritty a little bit. What is a value? How do we define these things? What do they look like? How are they different?

Modern value theory within psychology has been significantly shaped by the work of Israeli researcher Scholom Schwarz. He's considered the godfather of this field. Schwarz defined values as

"beliefs about trans-situational goals varying in importance, which serve as guiding principles in the life of a person or a group."

This definition might sound complex, so let's break it down.

Key Characteristics of Values

Linked with Emotion

Values are inherently emotional. By definition, they are considered the most important things in life. Consider, for example, the emotions displayed by protesters or the intense anger felt when someone wrongs you — these reactions are tied to your values being challenged.

Motivate Action

Values not only define what you want to pursue in life, but they also fuel the energy behind those pursuits. For instance, if you value status, it will not only guide your goals but also energize your actions and excitement about opportunities.

Apply Across Contexts

Values maintain their importance across different contexts. If you value honesty, it should hold true at work, in relationships, and with family. There's no context where you disregard your value if it’s truly a value.

Standards for Moral Judgments

Values serve as standards by which we make moral judgments, both of ourselves and others. For example, if personal freedom is a value, you measure yourself and others against this benchmark.

Ranked Hierarchically

People have a hierarchy of values that define their identities and guide their decisions. This hierarchy prioritizes what is most important to each individual.

Involve Trade-Offs

Prioritizing one value often requires devaluing others. For example, if you highly value personal freedom, you might place less importance on stability or routine, seeing them as constraints.

Core Questions Values Address

Values answer the fundamental questions of life: What matters? What is worth pursuing? What kind of person do I want to become? These are deep philosophical questions that define the essence of who you are.

Values vs. Psychological Needs vs. Preferences

Understanding Psychological Needs vs. Values

Let's clarify the differences between psychological needs and values as we move forward. Psychological needs are universal — we all have them in varying proportions. These needs are survival-based, such as the need for food. Without these needs being met, like food, survival becomes impossible, and there's no room for negotiation on this.

Similarly, there are certain fundamental psychological needs, such as social connection and belonging, that everyone requires. While the basic needs are the same for everyone, the strategies to meet them can vary vastly.

Values, as explained by Scholom Schwarz, serve as strategies to fulfill our psychological needs. For instance, while fulfilling the need for connection and belonging, some may lean towards values of benevolence and generosity, while others may focus on loyalty or group affiliation.

Differences Between Values and Preferences

Preferences differ fundamentally from values and psychological needs. Preferences are simple tastes or choices between non-impactful options, lacking deep emotional connection or identity reflection. For example, preferring steak over chicken does not constitute a value; it's merely a taste preference that holds no significant emotional weight or purpose.

Emotional Connection and Flexibility of Values

Values are tightly linked to emotions, changing throughout life based on experiences. They aren't static; they evolve as life's circumstances and personal insights shift. This changeability distinguishes them from the permanence of psychological needs.

It's crucial to recognize that values are not easily altered through logic or reasoning; they're deeply tied to emotional experiences and strategies developed during one's life and influenced by the surrounding culture and environment.

Empathy and Emotional Sensitivity in Values

Understanding values can enhance empathy. Recognizing that someone's differing values are their strategies for meeting their needs can reduce judgment. Values provoke strong emotions, be it in passion or discomfort, especially when questioned or challenged.

In this episode, the deep exploration of values might evoke such emotions, stirring reflection or even discomfort in the listener. This isn't a straightforward topic; it's central to personal identity and emotional well-being.

Values as a Potentially Unsettling Topic

Questioning one's values can be one of the most challenging yet enlightening psychological tasks. It's common for conflicts between values to arise in life, often addressed in the realm of therapy to navigate such complexities.

Sum Them Up

Finally, how these ideas affect your need for belonging or connection—factors like perceived security or need for novelty—vary individually. Each person’s psychological makeup determines their unique blend of needs and the values developed as strategies to meet them.

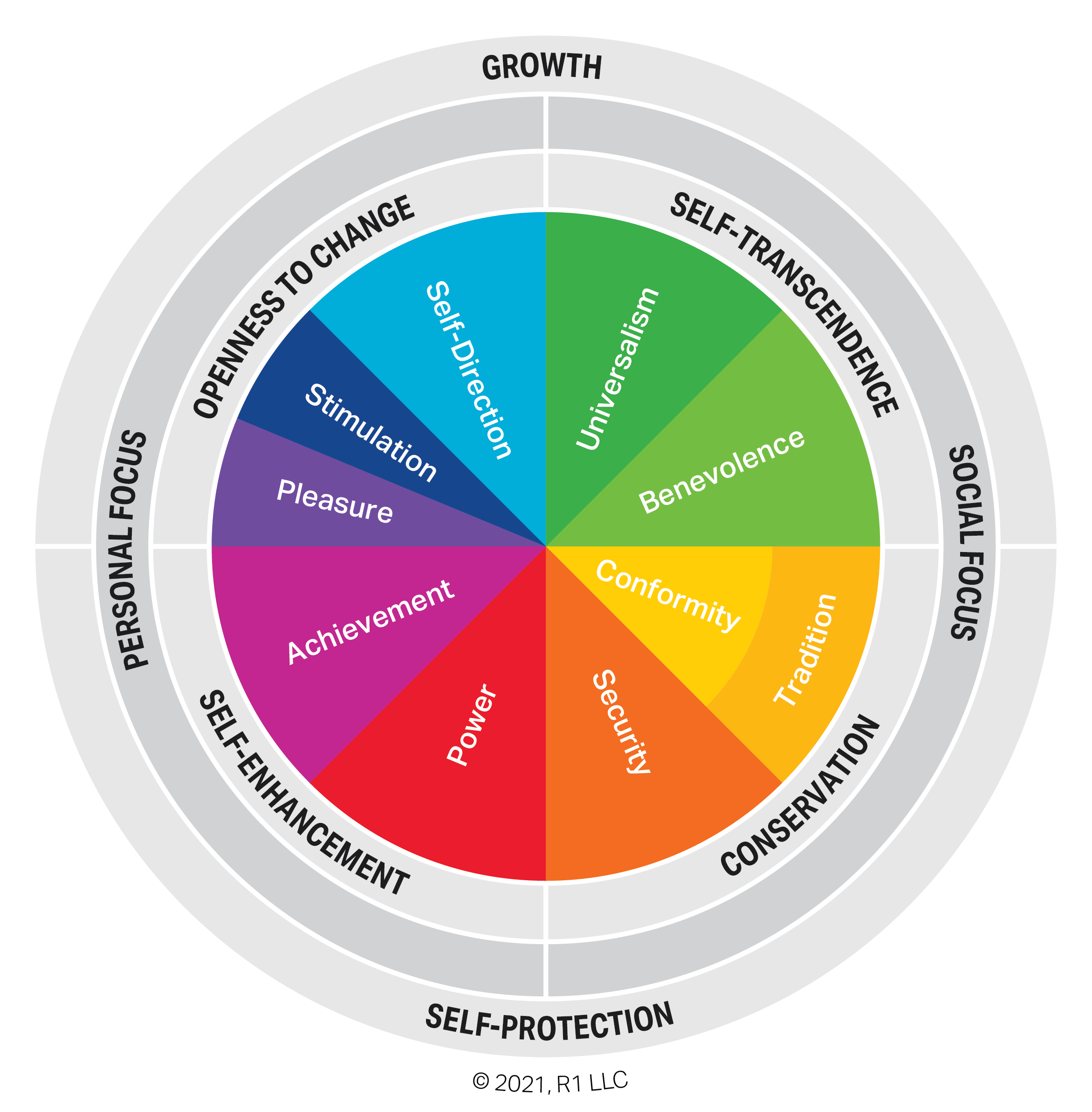

Schwartz's Values Wheel

Introduction to Schwartz's Values Wheel

We're going to explore multiple frameworks to help clarify the abstract nature of values. Understanding these should give you clarity on personal preferences and life challenges. We'll start with Schwartz's Values Wheel, which was developed through extensive cross-cultural surveys across more than 70 countries. This wheel defines ten core universal human values. We all possess these values, though in varying proportions, which influence our individual identities.

The Ten Core Values

- Self-Enhancement Values:

- Achievement: The drive for success and mastery.

- Power: The desire for control and influence.

- Conservation Values:

- Tradition: Respect for customs and cultural heritage.

- Security: The need for safety and stability.

- Conformity: Adhering to social norms and rules.

- Self-Transcendence Values:

- Universalism: A sense of unity with all people and the earth.

- Benevolence: The pursuit of altruism, charity, and kindness.

- Openness to Change Values:

- Stimulation: The seeking of excitement and novelty.

- Self-Direction: Personal freedom and independence.

- Hedonism:

- The pursuit of pleasure and enjoyment for its own sake.

Figure 1: Schwartz Model

The Wheel Structure and Internal Tensions

Schwartz placed these values in a wheel because of the inherent tensions between different value groups. Opposite groups on the wheel often have conflicting drives. For instance, values of "Openness to Change" conflict with "Conservation" values. Imagine individuals passionate about personal freedom; they are usually more open to change and exploration, often at odds with those who adhere strictly to tradition and security.

Another example of internal tension within the wheel is between the values of "Self-Transcendence" and "Self-Enhancement". While "Self-Transcendence" values emphasize group orientation and selflessness, "Self-Enhancement" values focus on personal achievement and power.

Synergy Among Neighboring Values

Values positioned next to each other on the wheel often harmonize well, such as "Universalism" and "Benevolence", or "Self-Direction" and "Stimulation". These adjacent values support one another, offering complementary pathways for personal development.

Political Compass Parallel

Interestingly, the dimensions of the Values Wheel parallel frameworks used in political science, notably the political compass, which evaluates political beliefs along similar axes. These parallels suggest that fundamental human value tensions are mirrored in larger societal and political structures.

Understanding and Navigating Internal Conflicts

Awareness of these internal tensions helps normalize personal conflicts we face. Recognizing which values are in conflict can help individuals understand difficulties they might experience, such as anxiety or sacrifice, in their pursuit of what they hold dear.

When faced with challenging decisions, consider which values each option represents and which values you are willing to compromise. This reflection can provide clarity and help accept past choices, understanding that sacrifices were made in favor of deeply held values.

Instrumental and Terminal Values

Introduction to Instrumental and Terminal Values

The second framework we're exploring is proposed by researcher Milton Rokeach from the 1970s. This framework distinguishes between two types of values: instrumental and terminal. Understanding this distinction offers clarity on our motivations and how we pursue goals in life.

Terminal Values

Terminal values are the end goals or ultimate values that you pursue for their own sake. They are considered terminal because they represent the ultimate objectives, with nothing beyond them. They are inherently valued without serving as a means to something else. These values are unconditional and intrinsic to our sense of purpose and fulfillment.

Instrumental Values

Instrumental values, on the other hand, are more means-to-an-end; they are valued because they lead you towards achieving a terminal value. They are steps or methods that guide you towards fulfilling your ultimate values. Although important, instrumental values gain significance primarily through their connection to terminal values.

Importance of Distinction

This differentiation is crucial, as people often confuse instrumental values for terminal ones. Such confusion can lead to misalignment in life choices and dissatisfaction. For example, making money might be perceived as an ultimate goal. Without linking it to a terminal value—like providing security for one's family—it can leave someone feeling unfulfilled and unsure of their purpose.

When individuals have clarity about their terminal values, they can find meaning in various roles and jobs, seeing them as instrumental in serving the larger purpose of their lives. Whether it’s working towards family security or personal growth, understanding the relationship between instrumental and terminal values can redefine how we perceive and engage with our daily endeavors.

Hierarchy of Values

Understanding the Hierarchy

This framework introduces the concept that our values exist within a hierarchy, with some being more foundational than others. At the top are our most important, guiding values, and beneath them are values adopted primarily to support these higher priorities. This hierarchy suggests that while certain values might appear essential, they often serve deeper, more meaningful objectives.

Navigating Value Tensions

Within the hierarchy, tensions often arise as we try to balance and prioritize values. Take, for example, achievement and benevolence. These values can sometimes conflict—prioritizing personal success may detract from helping others, and vice versa. However, achieving a balance where success enables more benevolent acts illustrates the dynamic nature of value hierarchies.

Flexibility Across Contexts

While inherent, these values need not be rigidly applied across all aspects of life. Depending on the context, certain values might take precedence. For instance, benevolence may be the focal value in personal relationships, while achievement might be emphasized in professional settings. Recognizing this flexibility can prevent the application of inappropriate values in unsuitable contexts.

Personal Reflections on Values

Personal experiences and self-reflection can bring insight into one's value hierarchy. Engaging with tools like the Schwartz Value Survey, individuals can gain clarity on which values resonate at the core level versus those adopted for instrumental purposes. This understanding reveals how value changes impact life direction, relationships, and priorities over time.

Evolution of Values Over Time

The dynamic nature of values means they evolve with life’s progression. What was once a core value might shift in significance, influencing daily habits, friendships, and personal pursuits. This evolution highlights the adaptability and ongoing development in one's value system, guiding decisions and life choices as circumstances change.

Discussion and Examples

Reflections on value assessments reveal common values such as self-direction and achievement, while others like hedonism may take a lower priority despite a lifestyle rich in stimulation. The conscious adaptation of values over time showcases the individual journey each person undertakes to better align their actions with their changing priorities and life stages.

Values Conflict

Introduction to Values Conflict

Values conflict arises when our deeply held beliefs and priorities come into competition, creating internal tension and challenging our ability to make decisions. Understanding and navigating these conflicts is a critical aspect of personal development, as our values cannot all be optimized simultaneously.

Examples of Values Conflict

- For someone who has benevolence as a high value, like wanting to help others, this can cause tension with personal goals such as achievement or self-care. Such individuals might struggle with saying "no," leading to overcommitment and burnout. As responsibilities grow, prioritizing certain aspects over others can compound the tension.

- In another example, personal values like self-direction and achievement might overshadow social connections and community involvement. While professional success might fulfill the desire to help others indirectly through work, it often leaves personal relationships sidelined, leading to sacrifices that can feel like sacrificing one value for the sake of another.

The Role of Trade-offs and Prioritization

Schwartz's Values Wheel highlights that all values come with inherent trade-offs. In real life, making choices about which value to prioritize often means sacrificing another. This necessitates difficult adult decisions, particularly when neither option is less significant.

Navigating Internal Tension

Many individuals wrestle with values conflict, sometimes seeking therapy for guidance. Common dilemmas involve balancing social justice advocacy with academic achievement or managing professional aspirations with personal relationships. These conflicts are challenging because they involve elements you deeply care about, yet they pull you in opposite directions.

Conclusion

Recognizing the trade-offs that come with value-based decisions helps normalize these internal conflicts. It's essential to understand that prioritizing values is a constant balancing act, where some degree of sacrifice is inevitable. Through this awareness, individuals can make more informed and peaceful decisions about where to direct their energy and devotion.

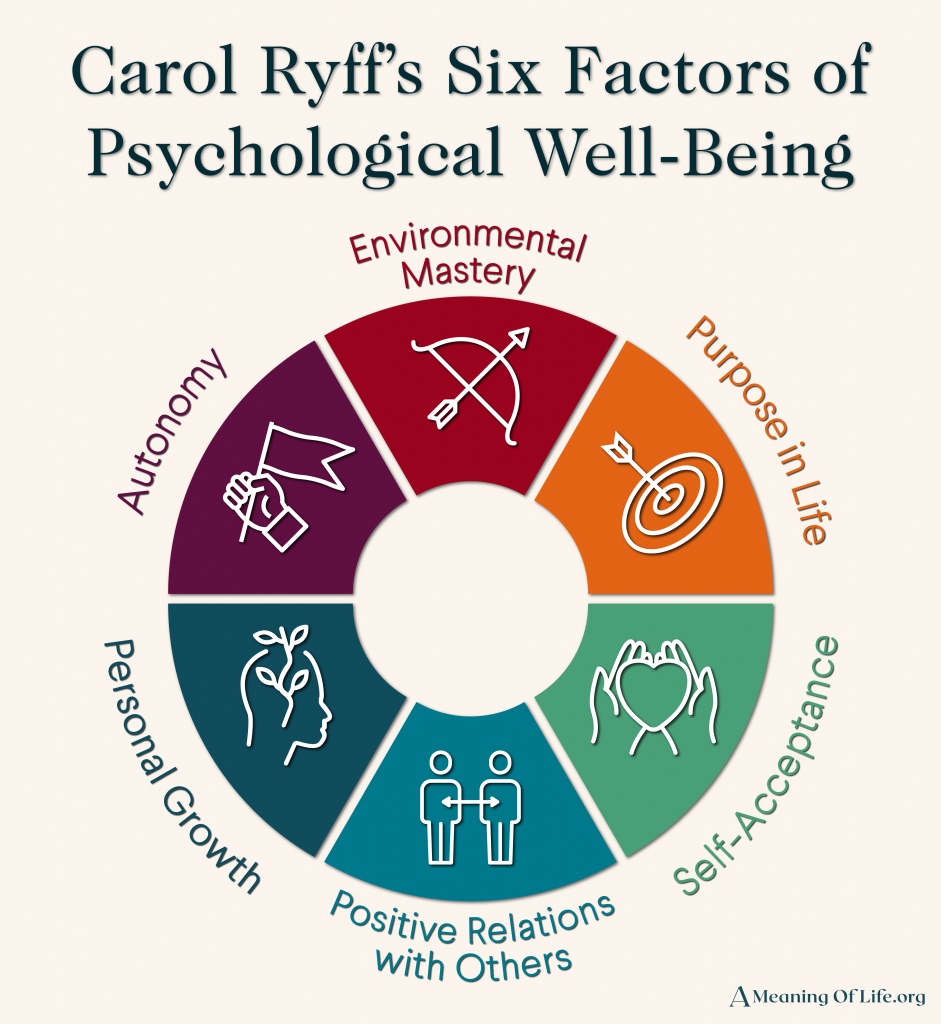

Carol Ryff's Six Dimensions of Psychological Well-being

Exploring Psychological Well-being

Carol Ryff's framework offers a comprehensive perspective on values by identifying dimensions that contribute to psychological well-being and human flourishing. This contrasts with other frameworks that often focus on trade-offs between values. Ryff's dimensions aim to outline what constitutes "good" values that promote overall health and happiness.

The Six Dimensions

- Autonomy: This involves being self-directed, resisting social pressures to conform, and acting based on personal values. High autonomy reflects not caring overly about external validation, while low autonomy reflects dependency on others' opinions.

- Environmental Mastery: This dimension is about competence and effectively managing life's demands. Individuals scoring high here feel capable and resourceful in navigating their environment, while those with low scores feel powerless and out of control.

- Personal Growth: Emphasizing lifelong learning and openness to new experiences, individuals high in personal growth constantly seek self-awareness and improvement. Low scores indicate a lack of interest in learning or evolving over time.

- Positive Relations with Others: This dimension focuses on the ability to form trusting, meaningful relationships where connections are valued for their own sake rather than being instrumental. Low scores can indicate feelings of isolation and difficulty in forming bonds.

- Purpose in Life: Individuals high in this dimension possess clear goals and a strong sense of direction, finding meaning in past and present experiences. Low scores are often associated with a lack of direction and feeling aimless.

- Self-Acceptance: This entails having a generally positive attitude toward oneself, owning one's flaws, and being realistic. High self-acceptance includes self-forgiveness without delusion, while low levels lead to self-criticism and dissatisfaction.

Figure 2: Carol Ryff's Six Dimensions

Integrating the Dimensions

Each dimension highlights values that contribute significantly to overall well-being. Unlike Schwartz's framework, which often includes inherent value trade-offs, Ryff's dimensions are seen as terminal values worthwhile in their own right. They form the foundation of human flourishing and are difficult to argue against as beneficial.

Application and Reflection

In practice, individuals may prioritize different dimensions according to their personal value hierarchy. For example, one might prioritize autonomy and personal growth, reflecting a focus on self-direction and achievement. These dimensions correlate with broader psychological frameworks and parallel concepts like a growth mindset and self-efficacy.

Challenges of Self-Acceptance

Of the six dimensions, many people struggle most with self-acceptance, as it involves facing one’s flaws and emotions honestly. It is believed that difficulties in other areas, like autonomy or personal growth, often have roots in a lack of self-acceptance. Recognizing and working on this dimension can therefore positively influence overall psychological well-being.

Aristotle's Golden Mean as Virtue

Introducing Aristotle's Golden Mean

Aristotle, the granddaddy of virtue ethics, defined virtue as a balance—a "golden mean" between two vices or extremes. Unlike modern frameworks that often measure values as quantities, Aristotle's approach emphasizes moderation. He suggested that every virtue stands between two deficiencies, advocating for a balanced approach to life.

Examples of the Golden Mean

Aristotle's concept can be applied across various virtues:

- Autonomy: Too much leads to isolation, while too little results in dependence. The virtue lies in having just enough autonomy to be independent yet connected.

- Courage: At its extremes, courage becomes recklessness or cowardice. The virtue is found in being brave yet cautious.

- Honesty: Excessive honesty can be offensive, while too little honesty leads to deceit. The golden mean ensures truthfulness without unnecessary bluntness.

- Generosity: Over-generosity can cause wastefulness, while stinginess is the opposite vice. A balance allows for kindness without personal detriment.

Applying the Golden Mean to Values

This framework is particularly valuable in avoiding overcommitment to a single value, which can lead to unintended negative consequences. A balanced approach can also help manage the inherent tensions between competing values. For example, the tension between generosity and frugality can be navigated by recognizing virtue in both sides.

The Interconnectedness of Values

Values don't exist in isolation—they function as a network that supports and enhances each other. For instance, courage without purpose reduces its significance, and generosity needs a target for its efforts to matter. Therefore, values gain meaning through their interrelationships.

Wisdom and Balance

Aristotle emphasized wisdom as a critical virtue, as it encompasses understanding and balancing other virtues. Wisdom helps detect when values are out of alignment and guides readjusting them for personal equilibrium.

The Individual Nature of Balance

Finding the right balance is a personal journey, depending on one's personality, needs, and values. Each person's "balanced" state will differ based on their unique preferences and priorities. Understanding one's intrinsic needs and the dynamics of their value network is crucial for achieving personal balance.

Ultimately, Aristotle’s Golden Mean encourages a harmonious existence where values complement and correct one another, promoting a well-rounded and fulfilling life.

Values and Your Relationships

A Case Study in Values Clash

This section explores how fundamental differences in values can significantly impact relationships. A friend shared a story about his relationship that highlights potential discord when partners have opposing values. They had contrasting lifestyles—he preferred intellectual, frugal, and relaxed experiences, while she leaned towards luxury and traditional expectations of gender roles.

The Importance of Aligning Values

Despite their mutual love for travel, their reasons for appreciating it clashed deeply, which became apparent during their trip. Their disagreements over spending and lifestyle preferences underscored that their relationship's issues weren't just about different interests but fundamental values. When core values such as financial perspectives and lifestyle choices differ significantly, finding common ground becomes challenging, if not impossible.

Navigating the Complexity of Values in Relationships

The conflict in this example serves as a reminder that shared interests do not always equate to shared values. Misalignments in values like money management, religious views, and approach to life can lead to conflict, which in turn affects relationship stability. Successful relationships often flourish when there is a complementary or supportive dynamic in values, allowing for balance and mutual growth.

Revealing Our Values Through Relationships

Relationships serve as a mirror, revealing our deepest values and sometimes challenging us to reevaluate them. Partners can help identify inconsistencies between stated values and actions, prompting personal growth and introspection. Experiencing discomfort in a relationship often highlights areas where values are misaligned or where personal growth is needed.

The Role of Communication and Self-awareness

To manage such conflicts, open and honest communication is vital, allowing partners to express their underlying motivations and needs. However, both parties must possess the self-awareness to understand their values and the maturity to communicate them effectively. Relationships can test our deeply held beliefs, assumptions, and motivations, guiding us towards personal clarity and growth.

Compatibility and Future Outlook

Imagining a future with a partner requires aligned goals and compatible values. When partners envision incompatible futures, staying together becomes difficult. Relationships force us to confront what we care about and what we prioritize in life, underscoring the importance of aligning values with personal and shared life goals.

The Clash of Values in Relationships

Understanding Value Clashes

Misalignment in values often becomes a critical point of tension in relationships. It's not unusual for partners to mistake differences in interests or preferences for value clashes. However, true value differences—rooted in fundamental beliefs and priorities—pose greater challenges and require deeper understanding and navigation.

Personal Growth in Navigating Values

As one matures, understanding and respect for differing values can improve. Early on, there might be a tendency to prioritize personal values, such as autonomy and independence, potentially at the expense of the relationship. Recognizing and respecting your partner's values can lead to more harmonious relationships. Sometimes, stepping back to understand motivations behind behaviors can shed light on these values and foster more empathetic interactions.

Compromise and Relationships

Long-term relationships require compromises. However, constant compromise to the detriment of personal values can lead to a loss of identity and dissatisfaction. Finding a balance where stable and healthy relationships coexist with personal values is essential. Sometimes, it involves turning down the intensity of certain values to give room for others that sustain the relationship.

Changing Values Over Time

Our values and priorities often evolve with experience. For example, the appeal of novelty and excitement in a relationship might initially be strong, but over time, stability and consistency become more valued. Recognizing this shift and adapting your value system is integral to sustaining long-term relationships. Both partners in a relationship must adapt and acknowledge these evolving values for continued harmony.

Relationship and Value Hierarchy

Interestingly, placing a relationship at the pinnacle of our value hierarchy can undermine it. When a person becomes too focused on the relationship, they might overcompromise, eroding their own identity and the authenticity of the relationship itself. Maintaining individuality within a relationship preserves the core traits that initially attracted partners to each other, contributing to ongoing intimacy and connection.

In conclusion, understanding and navigating value differences, making strategic compromises, and allowing for the natural evolution of values are crucial for healthy relationships. Avoiding the trap of over-prioritizing the relationship itself ensures a balance that fosters both personal growth and shared happiness.

Identifying and Navigating Values in Relationships

Advice for Recognizing Values

When entering a new relationship, it's crucial to differentiate between shared interests and core values. Interests are the activities and preferences that may initially bring people together, but it's the underlying values that ultimately determine compatibility. Observing signals early on, like expensive tastes or lifestyle choices, offers insights into a person's values.

Early Conversations About Values

To avoid unforeseen conflicts, prioritize discussing values early in the relationship. Within the first few dates, aim to delve into topics like attitudes toward money, motivations, religious beliefs, family outlook, and future aspirations. These discussions help determine if your core values align, potentially saving both parties from future heartbreak.

The Role of Respect in Values

Even if partners don't share identical values, mutual respect for each other's values is essential. Open, honest conversations about differing values can lead to a mutual understanding and respect, fostering a healthy relationship. Disrespect or dismissal of a partner's values often leads to a breakdown in communication and willingness to compromise.

Filtering for Compatibility

Filter for compatibility by asking questions that reveal what truly matters to both partners. While it's important to approach these discussions appropriately, understanding motivations behind interests provides a clearer picture of whether you're likely to find long-term compatibility.

Building a Foundation on Respected Values

Ultimately, the success of any relationship is more about the degree to which partners can respect each other's values than about sharing the exact same ones. Respecting a partner's values enables healthy compromise and growth, making this foundational to navigating values within any relationship.

Understanding Compatibility Through Values

Tools for Exploring Compatibility

Using tools like decks of cards with value-based questions can be a fun and insightful way to assess compatibility in relationships. Such tools are designed to prompt discussions that reveal core values and preferences, helping couples determine their compatibility. Engaging with these questions can fast-track understanding and highlight potential areas of alignment or divergence early in the relationship.

The Role of Familiarity in Long-term Relationships

Over time, couples who have been together for many years, like the speaker and his wife, often develop a deep understanding of each other's values. This familiarity creates a sense of stability and comfort that enhances the relationship. Even if partners don't share all the same values initially, adapting and balancing each other's values over time contributes to a profound connection and security that is unique to long-term partnerships.

Adaptation and Balance

As relationships progress and partners adapt to each other's values, they often reach a point where their differences are not obstacles but sources of balance and strength. This adaptation process can lead to significant relationship stability, providing a foundation that allows partners to thrive both individually and as a couple. The experience of seamlessly understanding each other's needs and preferences, highlighted by activities like the Newlywed Game, reflects the depth of connection that emerges from shared life experiences.

Long-term Fulfillment

The profound feelings of security and gratification that come from such balanced relationships offer a unique fulfillment. This dynamic underscores the importance of compatibility through values, showing that when couples effectively navigate and integrate their values, they can enjoy a partnership that not only survives but thrives over time.

Where Do Values Come From?

In this chapter, we'll briefly explore the origins of values. It's a fascinating topic with a rich research background, and while it's easy to get immersed in the details, we'll aim to provide an overview before moving on to practical advice.

Historically, the concept that values can significantly differ among individuals and cultures is relatively modern. During the colonial period, there was a dominant, non-pluralistic view, primarily led by Europeans who often imposed their values on others, dismissing the local beliefs as inferior or "savage."

It wasn't until the 20th century that a broader recognition and acceptance of value diversity began to emerge, acknowledging the wide range of values shaped by different cultures and experiences. This shift has provided a deeper understanding of human values and the complex factors that influence them.

Margaret Mead's Cultural Relativism

Margaret Mead, a pioneering anthropologist in the 1920s, challenged traditional Western views on cultural norms through her research on Samoan society. During a time when few female academics existed and travel to remote cultures was uncommon, Mead went to a Samoan village to study the local tribe's cultural values and behaviors.

Upon observation, she noted surprising differences: Samoan teenagers appeared less inhibited and happier compared to their European and North American counterparts. They exhibited greater sexual openness without judgment or social stigma, a stark contrast to the conservative and restrained Western values of the time.

Her findings suggested that many values perceived as inherent in Western society were actually culturally relative. This idea—that values vary across cultures—sparked significant controversy, as it challenged the prevailing belief in a universal set of Western norms and values.

To support her theory, Mead conducted further studies in New Guinea, observing three tribes with vastly different values and social structures. These findings reinforced her argument that values are largely shaped by cultural surroundings and are not absolute.

Mead's work prompts an awareness of how many of our values are inherited from our environment—be it family, community, or culture—rather than consciously chosen. Understanding this distinction between inherited and chosen values is essential for personal growth and self-awareness.

For individuals, travel and exposure to diverse cultures can reveal which values are flexible and which are non-negotiable. This exposure helps distinguish between values we've adopted because of our upbringing and those we actively choose to uphold. The journey of recognizing and questioning these values can lead to greater understanding and adaptation, highlighting the diverse ways societies organize and define what is important.

Mary Douglas's Grid-Group Framework

Building on the work of Margaret Mead, Mary Douglas introduced the Grid-Group Framework to map out cultural values and categorize different societies. Her framework consists of two dimensions: "grid" and "group."

High-Grid vs. Low-Grid Cultures

- High-Grid Cultures: Emphasize strict rules and a hierarchical respect for authority. These societies prioritize order and structure.

- Low-Grid Cultures: Rely more on individual freedom and independence, often exhibiting a more libertarian spirit with less rigid constraints.

In the same time:

- High-Group Cultures: These are collectivist societies that prioritize communal goals over individual desires. The individual's interests are often aligned with the group's well-being.

- Low-Group Cultures: Characterized by individualism, where personal goals and achievements are prioritized over group cohesion.

Douglas's framework closely parallels other models discussed in this episode, such as the political compass and Schwartz's values of self-transcendence versus self-enhancement. These inherent tensions—between order and freedom, collectivism and individualism—recur across various contexts, demonstrating similar patterns in both individual and societal values.

Cultural Values and Trade-offs

Mary Douglas emphasized that cultural values result from specific societal choices, reflecting preferences and trade-offs that form societal norms and taboos. Just as individuals grapple with balancing their values, societies must navigate trade-offs among collective values to maintain balance.

Challenges of Cultural Relativism

Cultural relativism, as presented by Mead, argues against absolute right or wrong, seeing morality as culture-dependent. However, it can become contentious when addressing extreme practices like slavery or human sacrifices. These extremes highlight the risk of overemphasizing a single value, leading to neglect or harm to other important values.

Aristotle's concept of the golden mean is applicable here, suggesting that a balanced approach—neither excessive nor deficient—is essential for morality. This balance applies to societal values as well, where extremes on any axis can harm the broader value network.

Interdependencies and Challenges

Societies, like individuals, navigate their own complex value networks, where overt focus on one value, such as family in some Latin American and Asian cultures, can lead to systemic issues like corruption. This example illustrates how cultural values must be balanced to avoid adverse outcomes.

Douglas's framework underscores that values are deeply embedded in our social and cultural environments. While many values are inherited, they are also shaped by the social structures and institutions surrounding us. This understanding highlights the intricate balance between nature and nurture in value formation and the potential for societal change.

Jonathan Haidt's Moral Foundations Theory

Jonathan Haidt's Moral Foundations Theory offers a perspective on the innate components influencing our values and moral judgments. Haidt suggests that just as we have taste buds for different flavors, our moral frameworks are shaped by foundational "moral taste buds" that guide our perceptions of right and wrong.

The Six Moral Foundations

Haidt identifies at least six primary moral foundations:

- Care vs. Harm: Focus on nurturing and protecting others.

- Fairness vs. Cheating: Concerned with justice, rights, and equality.

- Loyalty vs. Betrayal: Valuing allegiance to one's group or community.

- Authority vs. Subversion: Preference for order and respect for tradition.

- Sanctity vs. Degradation: Emphasizing purity and sacredness.

- Liberty vs. Oppression: The desire for freedom from control and domination.

These foundations are thought to have evolved to help humans live in cooperative groups. Each individual possesses all these moral taste buds, but cultural and individual differences influence which ones are prioritized.

Interplay Between Genetics and Culture

While cultural environments strongly influence which moral values are emphasized, there is likely a genetic basis to these predispositions. For instance, liberals typically prioritize the care and fairness foundations, while conservatives utilize a broader spectrum, including loyalty, authority, and sanctity.

Emotions as Drivers of Moral Values

Haidt emphasizes that moral values are deeply rooted in emotional responses. His analogy of the "elephant and the rider" illustrates that our emotional instincts (the elephant) often guide our behavior, while our rational mind (the rider) post-hoc justifies these actions. Rarely do logical arguments shift core values; instead, values are fundamentally emotional.

Different Conceptions of Fairness

Liberal and conservative perspectives on fairness reflect fundamental differences. Liberals often see fairness as equality or equity, ensuring everyone has similar opportunities, while conservatives view fairness as proportionality, rewarding individual contribution.

Societal Balancing Act

Haidt's theory aligns with Aristotle's golden mean concept, reinforcing the idea that a balanced set of values is essential for both individuals and societies. Extremes in any direction have drawbacks, and historical events illustrate how overemphasis on particular values can lead to societal imbalance and necessary corrections.

The intertwining of individual morals with societal values reveals an intricate web of interaction, suggesting that a healthy balance of these moral foundations is crucial for collective well-being.

The Allegory of the Taco Truck

This story, set at a taco truck, serves as an illustrative metaphor for how different value systems come into play in everyday situations, revealing the complex nature of human interactions.

The Incident

The narrator recounts an incident where he, his girlfriend, and another patron at a taco truck experienced a conflict rooted in differing value priorities. While sitting at the picnic table, they observed a man reaching into the tip jar, presumably to reclaim a tip for bus fare. A bystander, unaware of the man's mental disabilities, perceived this as theft, resulting in a heated exchange.

Conflicting Values at Play

- Care and Harm: The narrator, having interacted with the man and understood his situation, responded based on the value of care, feeling a protective empathy toward him.

- Fairness and Cheating: The bystander was driven by a sense of fairness, perceiving the act as cheating and reacting based on the violation of that principle.

- Order and Calm: The narrator's girlfriend sought to maintain peace and order, driven by her value for calm and stability, which had been disrupted by the escalating tension.

Reflections on the Event

From a detached perspective, the narrator later realized that each person acted according to their values, none of which were inherently wrong. Instead, it was a situation where different moral foundations were triggered, leading to the conflict. This reflection emphasizes how values can drive behavior and interpretations in ways that are deeply personal yet universally relatable.

Microcosm of Broader Conflicts

Such situations frequently occur in daily life, where individuals may clash not because their viewpoints are fundamentally incorrect, but because their underlying values differ. This recognition can lead to more understanding interactions, as it shows that apparent conflicts often stem from diverse value systems rather than objective right or wrong.

The "Allegory of the Taco Truck" thus serves as a reminder of how complex and situational values can be, mirroring larger societal and political divisions on a smaller scale. Understanding this can foster empathy and temper reactions in the heat of the moment.

Identifying Your Core Values

As we transition into this chapter, we're moving from theory and discussion into practical application. So far, we've explored what values are, their significance, their origins, and the ways they manifest in our lives. Now, it's time to delve into a more personal exploration: identifying your core values.

This section will guide you in determining what truly matters to you by exploring exercises and methods designed to bring clarity to this sometimes ambiguous aspect of personal identity. Recognizing your core values can be challenging, given their often elusive nature and the layers of influence from various life experiences.

We'll provide practical exercises to help unearth these foundational elements of who you are. Additionally, for those seeking a more structured approach, there's an extended 30-day program available through the Momentum Community, offering detailed guidance and support for discovering, acting upon, and adapting your core values. This journey of self-discovery and value clarification is vital for aligning your actions with your deepest beliefs and aspirations.

Thought Experiments to Find Your Values

Desert Island Visualization

One effective thought experiment for discovering your core values is the "Desert Island Visualization." Imagine yourself alone on a desert island with all material needs provided. Here, free from societal influences and pressures, consider what activities you would engage in. This exercise helps highlight intrinsic values by removing external pressures. If your imagined activities differ significantly from your current lifestyle, it may indicate that you are living according to others' values, not your own.

For example, someone might realize that they would still prioritize reading and creative pursuits, revealing genuine personal values. Conversely, a significant discrepancy between your desert island activities and daily life suggests the need to realign with authentic values.

Funeral Visualization

In contrast, the "Funeral Visualization" exercise considers your legacy. Imagine attending your own funeral and reflect on what you hope people will say about you. This thought experiment focuses on the social impact and legacy you wish to leave behind, encouraging introspection about how you want to be remembered.

For instance, if you desire people to say you were generous and gave more than you took, it points to benevolence as a core value. This exercise can provide clarity on the values you aspire to embody and the influence you wish to have on others.

Identifying Frustrations as Value Clues

Another technique involves analyzing recurring frustrations or pet peeves in your life. These often indicate underlying values that are unmet or challenged. For instance, if incompetence consistently irritates you, it may reflect a strong value for competence and mastery.

Ranking and Prioritizing Values

Finally, prioritize values by comparing them directly. When forced to choose between two values (e.g., honesty versus competency), note your gut reaction. This common thought experiment helps clarify which values hold more significance to you. These decisions often occur at a visceral level, highlighting the deep-seated nature of values.

Disposition vs. Aspiration

Discussing the nature of values brings up whether they are dispositional (innate) or aspirational (ideal-based). While values likely have genetic and social components, they can be adjusted over time to some extent. Achievement and community might serve as an example where values can shift more incrementally towards desired aspirations.

Overall, these exercises encourage an exploration of intrinsic motivations, leading to a deeper understanding of what truly matters, while recognizing the potential for gradual adaptation and growth in personal values.

The Instrumental Value of Golf

This fable about Tiger Woods serves as a humorous and enlightening tale about recognizing what we truly value in life versus the instrumental value of certain activities.

The Story

The narrator recounts an opportunity to play golf with Tiger Woods and Will Smith—a chance presented due to their mutual friendship. The narrator, not being a golfer and disinterested in the sport, initially declined the invitation due to the pressure of embarrassing themselves on the course. Unbeknownst to them, they were missing out on an exclusive opportunity for personal networking and bonding.

The realization dawned afterward: golf, beyond being a sport, serves as a powerful social tool among successful individuals, facilitating intimate conversations and relationship building. Inspired by the missed chance, the narrator briefly considered learning golf to access these networking opportunities.

Realization and Reflection

Despite attempts to get into golf, including lessons and outings with friends and family, the narrator found no joy in the game itself. This led to an important realization: the motivation to play golf was driven by its perceived instrumental value, not an inherent interest in the sport. The narrator valued the social and professional opportunities golf presented, not the activity itself.

Interpretation

The fable highlights the difference between instrumental values and intrinsic values. It underscores the importance of pursuing activities that align with our genuine passions and values rather than engaging in pursuits solely for their potential benefits. In life, understanding this distinction is crucial for making choices that are fulfilling and aligned with our true interests.

Broader Message

As this anecdote illustrates, examining our motivations and understanding the difference between intrinsic enjoyment and instrumental gain can guide us toward more authentic and satisfying life decisions. It's a reminder to prioritize genuine values over activities adopted purely for their perceived advantages.

The Role of Trauma in Value Change

One of the pivotal ideas in understanding personal growth is recognizing how trauma and adversity can lead to significant shifts in our values. While we often focus on what we desire and aspire to gain, true value change comes from what we are willing to sacrifice.

Choosing Your Struggle

The concept of "choosing your struggle" emphasizes that values aren't just about desire but about what we're ready to prioritize and sacrifice for. The highest values in our hierarchy are those we are willing to give up other things for. This helps explain why life changes are often catalyzed by negative events or trauma, forcing us to reevaluate and re-prioritize our deepest values.

Post-Traumatic Growth Theory

Post-Traumatic Growth Theory explores how individuals often report positive changes following traumatic experiences. Research indicates that 80-90% of people note at least one positive shift in their lives after a trauma. This isn't to romanticize trauma; rather, it shows human resilience and the ability to thrive despite adversity.

Trauma forces a reassessment of values, as it often exposes the failure of previously held beliefs. In this re-evaluation process, individuals may:

- Improve relationships with others,

- Discover new possibilities in life,

- Develop increased personal strength,

- Gain a greater appreciation for life,

- Experience spiritual or existential growth.

The Vacuum Left by Trauma

Traumatic events create a void where old values or beliefs fail. This void presents an opportunity for growth, requiring new values to fill the space. While this process is often painful and challenging, it opens the door to meaningful change.

Example of Value Shift

A common scenario is someone facing a terminal illness, catalyzing a shift from values like career success to more personal ones like family and relationships. This stark contrast makes individuals reassess what truly matters, prompting a reprioritization of values.

Holding Positives and Negatives Together

It's important to acknowledge that positive value changes can accompany the enduring negative impacts of trauma. These changes aren't exclusively favorable, nor do they negate the challenges of the trauma itself. For example, cancer survivors might report increased gratitude post-recovery, highlighting the coexistence of trauma's dual nature: painful yet sometimes growth-inducing.

In summary, trauma challenges our existing values and beliefs, often serving as a powerful catalyst for personal growth and value transformation. Recognizing this dynamic helps individuals navigate life’s complexities with a deeper awareness of what truly matters to them.

How to Change Your Values

In this chapter, we'll explore the process of value change, acknowledging the undeniable influence of experiences, particularly traumatic ones. While traumatic events can sometimes lead to shifts in values, the extent and nature of this change depend on various factors, including personality traits, coping strategies, and the nature of the event itself.

For those with optimistic outlooks or openness to new experiences, change is often more attainable. An effective coping style known as "active rumination" plays a significant role in post-traumatic growth. This involves deliberately engaging with one's thoughts and emotions following a traumatic event, facilitating cognitive reappraisal and the exploration of how such experiences can challenge or reshape existing values.

Another crucial factor in fostering positive value change is one's social environment. A supportive network—whether family, friends, or community—can significantly influence the likelihood of positive growth following trauma. Being surrounded by individuals or a culture that encourages open discussion, reflection, and reinterpretation of trauma can be pivotal in navigating value changes effectively. This support network offers the encouragement and perspective needed to reshape values in a constructive and affirming manner.

Kazimierz Dabrowski and Positive Disintegration

Kazimierz Dabrowski, a renowned yet lesser-known psychologist, introduced the concept of "Positive Disintegration," offering a unique perspective on personal growth through adversity. Working in post-World War II Poland under Soviet occupation, Dabrowski focused on tragedy and trauma, diverging from the Western psychological focus on self-esteem and happiness.

Concept of Positive Disintegration

Dabrowski observed that many Holocaust survivors and Polish war veterans reported significant personal growth after enduring immense trauma. Though initially experiencing despair, some survivors expressed that post-tragedy, they became better individuals—more grateful, ambitious, and connected to others. Dabrowski termed this process "positive disintegration," positing that trauma causes a disintegration of the ego, shaking core beliefs and values.

This ego destruction leaves a vacuum that, if filled with more adaptive and healthy values, fosters growth. The traumatic event essentially forces a re-evaluation of one's value system, leading to personal development.

Legacy and Impact

Dabrowski's work remained largely unknown for decades due to geopolitical barriers until it was revitalized by researchers in the early 2000s. His theory aligns with concepts like post-traumatic growth, emphasizing how crisis can lead to re-evaluating and strengthening values.

Personal Stories of Positive Change

The discussion also highlights personal experiences of value transformation through trauma. For instance, a family loss prompted a deeper appreciation for family values, while another recounted the tragic loss of a friend, which spurred a significant life realignment toward responsibility and achievement.

Cultural Influences on Value Re-evaluation

Research suggests that individualistic cultures, like the U.S., often lead to re-evaluation towards self-focused achievements, while collectivist cultures emphasize societal and moral duties. This illustrates the interplay between personal experiences and larger cultural contexts in shaping our value transformations.

Overall, Dabrowski's theory of Positive Disintegration underscores how adversity can catalyze profound personal growth, encouraging a redefinition of priorities and fostering resilience through conscious re-evaluation.

On Cults and Cognitive Dissonance

Cognitive dissonance, a concept introduced by psychologist Leon Festinger, plays a crucial role in understanding how and why our values change—or why they may stubbornly remain the same. Cognitive dissonance occurs when there's a disconnect between our beliefs and experiences, creating mental discomfort that we are motivated to resolve.

The Story of Festinger’s Research

In an iconic study, Festinger infiltrated a cult led by Marian Keech, who predicted an imminent alien invasion. The researchers observed that when the prophecy failed, rather than abandoning their beliefs, the cult members doubled down on their commitment. They interpreted the lack of an invasion as a success of their efforts, amplifying their dedication.

Cognitive Dissonance and Belief Change

When faced with contradictory evidence to their beliefs, individuals experience dissonance, which they can resolve either by rejecting the new reality or by modifying their beliefs. This mechanism explains why cult members, faced with a failed prophecy, choose to strengthen their commitment rather than abandon their faith. Leaving the cult means losing the community and purpose it provides, which is often too painful to consider.

The Role of Values in Cognitive Dissonance

Values are strategies to meet needs, and fundamental psychological needs such as belonging and purpose are often intertwined with our values. For those in a cult, these needs are fulfilled by their beliefs, making it difficult to change without experiencing significant personal loss.

Leveraging Cognitive Dissonance for Positive Change

To change your values intentionally, induce cognitive dissonance by taking tangible actions that align with desired values—even if they initially feel unnatural. By consistently acting on these values, the accompanying dissonance will eventually realign your beliefs to match your actions, reshaping your value hierarchy.

For example, deciding to prioritize family by spending more time with them can initially feel discordant with other priorities. However, as you invest more energy into these actions, your values can shift to reflect this new focus.

Understanding Values in Argument and Discourse

Cognitive dissonance also impacts discourse, particularly in heated arguments or political debates. Often, conflicts arise from misaligned values rather than factual discrepancies. Successful dialogue requires recognizing and addressing the correct underlying values rather than challenging surface-level beliefs.

The complexity of value systems means that even factual debates are deeply rooted in differing value prioritizations. Recognizing this helps to engage in more empathetic and productive conversations, focusing on common values rather than divisive facts.

Self-Confrontation and Value Change

Milton Rokeach, renowned for developing the concepts of instrumental and terminal values, further explored how individuals might change their values through self-confrontation. His research focused on prompting individuals to critically evaluate their own beliefs and reasoning, ultimately facilitating value change.

The Self-Confrontation Method

During the civil rights era of the late 1960s, Rokeach conducted studies involving individuals from different political backgrounds—those on the left valuing equality and those on the right emphasizing fairness, autonomy, and freedom. Participants engaged in reflective exercises, choosing between values like freedom and equality and writing essays defending their positions.

Reframing Values

Rokeach introduced a crucial step: reframing participants' cherished values within the context of the opposing value. For instance, he asked right-leaning individuals valuing freedom to consider civil rights activists' actions as a fight for freedom, albeit under the banner of equality. By encouraging participants to see their opponents' values as an extension of their own, he facilitated a surprising openness to new perspectives.

This exercise demonstrated that by packaging arguments in the values of others, even deeply held beliefs could be shifted, highlighting the power of value reframing in persuasion and self-reflection.

Implications for Persuasion

The success of Rokeach’s method underscores a critical aspect of persuasion: framing arguments in terms of the recipient's values can lead to more effective communication and transformative understanding. This approach might also be applicable in broader contexts, suggesting potential topics for exploring persuasion strategies in future discussions.

In summary, Rokeach's self-confrontation method illustrates the potential for thoughtful reflection and reframing to instigate meaningful changes in one's value system. By challenging individuals to examine their beliefs through the lens of alternative values, it encourages personal growth and a broader understanding of complex issues.

Charlie Munger's Maxim: Incentives and Behavior

Charlie Munger, celebrated as the business partner of Warren Buffett and known for his philosophical approach to investing, has an insightful saying: "Show me the incentive and I'll show you the behavior." This maxim underscores the powerful influence incentives have on our actions and how they intertwine with cognitive dissonance in shaping our values.

Linking Incentives and Cognitive Dissonance

We previously discussed how cognitive dissonance suggests that if you act according to a desired value—despite initial discomfort—your beliefs will eventually align with your actions. Munger's insight adds another layer: creating incentives can strongly influence the behaviors that align with those desired values.

Implementing Incentives

Consider the example of prioritizing family. If someone struggles to put this value into practice, a direct method could involve scheduling visits or calls. However, incorporating incentives could make this shift more compelling. For instance, rewarding oneself with a trip of choice for every visit made to family can motivate consistent action.

Equally applicable to fitness and nutrition, setting up rewards or penalties can facilitate healthier choices. Whether it's through gamification, collaborating with friends, or tracking progress, these incentives nudge us toward health-oriented actions. As these behaviors become routine, the cognitive dissonance resolves, reinforcing health as a core value.

The Power of Sacrifice and Prioritization

Ultimately, values are shaped by what we are willing to sacrifice. Munger's wisdom encapsulates the idea that identifying the right incentives can guide our behavior toward aligning with our true values. This framework not only reaffirms the connection between actions and beliefs but also highlights the significance of deliberate sacrifice in value prioritization.

By understanding and leveraging these strategies, individuals can effectively cultivate value-driven actions and make meaningful changes in their lives.

Lessons and Takeaways

As we approach the conclusion of the episode, it's essential to distill the key lessons and takeaways for applying the insights discussed. Aristotle's concept of "practical wisdom" offers a useful framework for understanding the application of values. He argued that wisdom is the most critical virtue because it allows individuals to balance and calibrate all other virtues. Wisdom helps determine when to emphasize or deprioritize a particular value, acting as the guiding force in managing our value hierarchy effectively.

To explore practical wisdom, we'll examine four key elements that contribute to gaining clarity on our values and living them authentically:

- Self-Awareness: Understanding your values necessitates clarity around what you prioritize. Self-awareness involves recognizing these priorities and questioning whether they align with your true self. Methods like journaling, therapy, and meditation can enhance self-awareness, aiding in the identification and evaluation of values.

- Emotional Regulation: Aligning emotions with values involves managing emotional responses to stay true to your priorities, especially in challenging situations. Techniques like Albert Ellis's Rational Emotive Behavioral Therapy (REBT) offer frameworks for understanding the interplay between events, beliefs, and emotional consequences, facilitating a values-aligned response.

- Social Relationships: Relationships significantly impact value manifestation. Leveraging social circles that respect and amplify your values helps maintain alignment. Awareness of how values influence interpersonal dynamics is crucial, ensuring that relationships are supportive rather than obstructive.

- Self-Acceptance: Carl Rogers highlighted the paradox that accepting oneself enables change. Embracing both strengths and vulnerabilities helps navigate the complexities of living according to one's values. Self-acceptance requires acknowledging imperfections and the inevitable discomfort accompanying value-centered living.

These principles constitute practical wisdom, empowering individuals to understand and embody their values constructively. By fostering self-awareness, regulating emotions, nurturing supportive relationships, and practicing self-acceptance, individuals can achieve a balanced and meaningful life grounded in their core values.

The 80/20 of Values

To conclude the episode, let's distill the core insights using the 80/20 principle, which states that 20% of our efforts often yield 80% of the results. Here's how this applies to understanding and working with values:

1. Clarity on Values

The most critical step is gaining clarity on what your values truly are. Whether through thought experiments, reflection on past decisions, or considering life’s challenges and frustrations, understanding what you genuinely value provides a foundation for self-awareness. This clarity alone sets you ahead of others who may not consciously assess their values.

2. Focus on Problems and Discomfort

Pay attention to the problems and discomforts in your life—they often highlight the values at play. The challenges you face are reflections of your value hierarchy. By understanding these issues, you can better determine whether your current values serve your long-term goals.

3. Self-Awareness and Emotional Regulation

Cultivate self-awareness to understand your reaction patterns, which helps align your emotions with your values. Recognize the significance of emotional regulation in maintaining value alignment, especially during challenging situations.

4. Relationship Dynamics

Examine friction points in relationships, as these can reveal value mismatches. Building relationships that respect and enhance your values requires understanding both your own and others' perspectives. Encourage diversity rather than conformity of values within your social circles.

5. Differentiating Values

Once you identify what matters to you, rank your values to distinguish higher priorities from lower ones. This helps make informed decisions about where to invest your energy and attention, ensuring alignment with your desired hierarchy of values.

6. Practical Wisdom

Develop wisdom to adapt your values flexibly as life circumstances change. Wisdom involves monitoring your value system, recognizing when adjustments are needed, and making those changes gracefully.

7. Cognitive Dissonance and Action

Recognize that values often follow action. To change your value hierarchy, take action aligned with your desired values, even if it feels uncomfortable at first. Overcoming initial resistance can lead to a realignment of your values and reduce cognitive dissonance.

Sum Them Up

By focusing on these key areas, you can significantly enhance the alignment of your actions with your core values, ultimately leading to a more fulfilling and balanced life.

What We Learned

Reflecting on the preparation and recording of this episode, several key insights emerged.

- Self-Awareness and Value Shifts: A significant takeaway was the realization of how much personal values can shift over time. As one ages, priorities change, and what seemed important in youth, like excitement and novelty, may yield to more enduring values. The importance of self-awareness in recognizing and adapting to these shifts cannot be overstated.

- The Interconnectedness of Values: Understanding the network of values and how they interlace with each other highlighted the potential risk of over-focusing on a single value at the expense of others. Achieving a balance, much like maintaining a diversified stock portfolio, can prevent excessive dependency or harm from over-indexing on one area.

- Cultural and Social Reflections: The reflection also extended to the broader cultural context, recognizing that tensions in values aren't necessarily conflicts between right or wrong but rather differences in prioritization. This perspective promotes empathy and understanding across various social and political divides.

- Communication in Relationships: The discussion underscored the importance of recognizing when disagreements are rooted in differing values. It emphasized the need to approach such situations by ensuring discussions occur on the same level and acknowledging the diversity of values rather than assuming an intellectual or factual disagreement.

- Applying Wisdom in Daily Life: The episode reiterated that practical wisdom involves continually monitoring and adjusting our values as life circumstances change. It’s about knowing when to elevate or demote values based on current priorities, ensuring our actions align with what matters most at the time.

Next Steps

For those inspired to delve deeper into understanding and realigning their values, the Momentum Community offers a structured 30-day program to support this journey. Engaging with such a community can provide the tools and accountability needed to make meaningful changes and foster personal growth.

By embracing these lessons and actively participating in value reflection, individuals can pave the way for a more fulfilling, value-driven life. The insights gained from this episode serve as a foundation for ongoing personal development and self-discovery.